Palace and collections

The museum displays artefacts unearthed during over a century of archaeological research.

Explore the museum and the most ancient history of Verona’s territory

Paleolithic

Shaman of Fumane

Shaman of FumaneNeolithic

In the Neolithic period, human groups changed their way of life, moving from a system based on hunting and gathering to agriculture and animal husbandry. This transformation was accompanied by other technological innovations, such as the working of clay (for the production of ceramic pots) and polished stone (for axes and ornaments) and the introduction of weaving. Larger open-air settlements appeared and the trading system expanded. Several settlements dating back to the Middle Neolithic period (5500-4900 BC) have been found in the Verona area, located in such a way as to be able to exploit both the plains for agricultural activities and the flint outcrops of the Lessini mountains.

Don’t miss: the ‘Venus’ of Rivoli Veronese. The statuette represents a form of ritual linked to the seasonal cycles of the agricultural world, based on the life cycle of death and rebirth. The figure, which has been interpreted as a “mother goddess”, is stylised and characterised by a few features (arms bent at an angle, hints of hair).

Venus of Rivoli Veronese

Venus of Rivoli VeroneseCopper Age

In northern Italy, between the 4th and 3rd millennia BC, a new technology emerged that used a raw material – copper – to make objects. In the final phase, between 2500 and 2000 BC, common elements became widespread throughout continental Europe, such as the characteristic “inverted bell” shape of vases (“bell-shaped glasses”) and symbolic elements of power and prestige, suggesting cultural integration between the different European societies of the time.

Don’t miss: the anthropomorphic stele. The stele-statues on display, found in Spiazzo di Cerna (Sant’Anna d’Alfaedo) and Sassina di Prun (Negrar), are characterised by a cylindrical body, a flat disc forming the head and a stylised face. They come from funerary contexts and probably served as grave markers or installations with a particular symbolic meaning.

Anthropomorphic stele

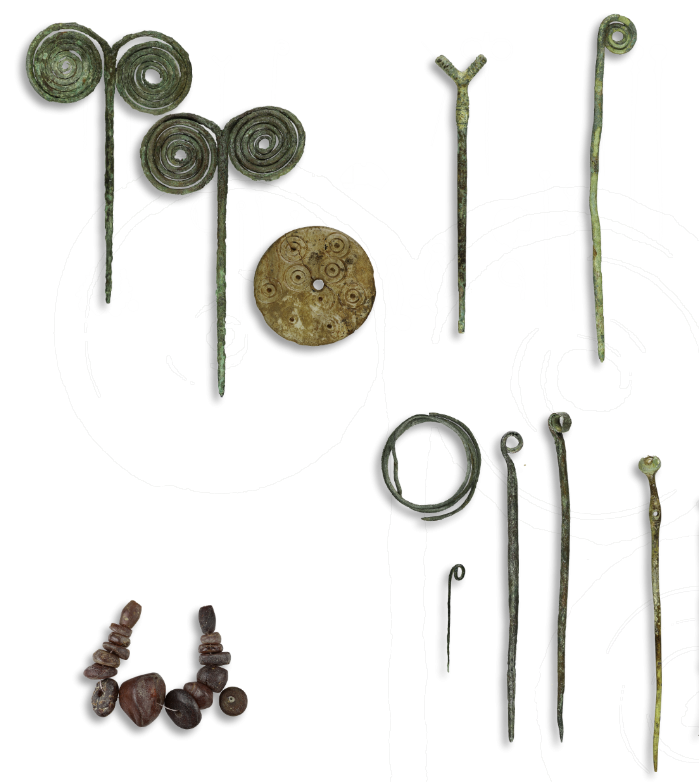

Anthropomorphic steleBronze Age

Between 2100 and approximately 950 BC, the use of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, became widespread in northern Italy.

During the Early Bronze Age (2100-1650 BC), important villages sprang up, some of which were built on stilts. During the Middle Bronze Age (1650-1350 BC), the first villages surrounded by embankments and moats developed, but it was mainly during the Late Bronze Age (1350-1150 BC) that the territory saw a population explosion and the development of large embanked sites, especially in the area of the Valli Grandi Veronesi. In the Late Bronze Age (1150-950 BC), after a period of crisis, there was a general reorganisation of the territory, with the flourishing of the settlements of Gazzo Veronese and Oppeano, which would also be important in the subsequent Iron Age. The museum also displays a selection of materials from some of the richest necropolises found in the Verona area, such as Cellore d’Illasi, Olmo di Nogara, Scalvinetto and Desmontà di Veronella.

Don’t miss: materials from the pile dwellings. The humid storage conditions have allowed organic materials, which normally degrade, to survive, helping us to understand the lives of human groups during this period. The materials on display in the museum come from several pile-dwelling sites that became part of the World Heritage Site in 2011.

Iron Age

In addition to the use of iron, societies became increasingly complex during this period and the first true urban forms developed. The foothills of the Veronese territory (Lessini, Valpolicella and the hills east of Verona) are linked to the Rhaetian Alpine world, while the low plains saw the birth of two centres belonging to the culture of the “ancient Veneti”: Gazzo Veronese and Oppeano. Between the 7th and 5th centuries BC, Gazzo Veronese became the real bridgehead of the Venetian populations with the Etruscan world.

Between the end of the 5th and the beginning of the 4th century BC, populations of Cenomani Gauls (“Celts”) from beyond the Alps settled in the Verona area. Little is known about their settlements, but grave goods show an abundance of weapons and items typical of banquets, along with a gradual assimilation of cultural models, coins and materials from central Italy.

Don’t miss: the tomb of ‘the child prince’ of Zevio. An exceptional find in the necropolis of Lazisetta di Zevio is the burial of a child aged 5-7, undoubtedly of princely lineage, whose ashes were laid to rest together with a sumptuous parade chariot and a large collection of grave goods typically associated with adult warriors. Inside some vases were the remains of pig bones, leftovers from the funeral banquet.

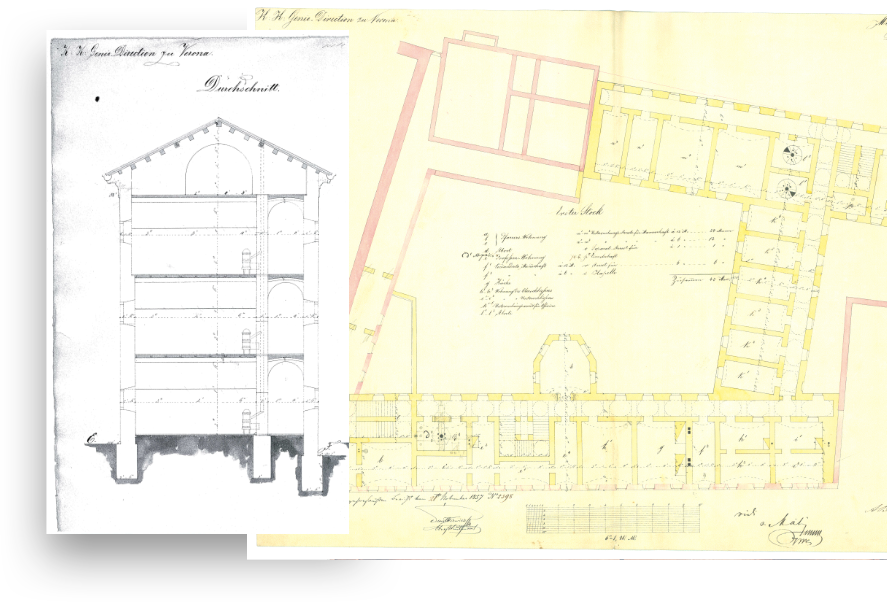

The Palace

The architectural complex is one of the best-preserved examples of Austrian civil architecture in Verona.

Before the current building, the area adjacent to the 15th-century church dedicated to St Thomas Becket was occupied by a convent of the Calced Carmelites, dating back to the 13th-14th century, which was then nationalised during the Napoleonic era. Between 1844 and 1848, during Austrian rule, the structure was converted into a place of detention, where many subversives were imprisoned following the Carbonari uprisings. Prominent figures of the Veronese Risorgimento, remembered as the “Martyrs of Belfiore”, were tried and detained here: a group of patriots sentenced to hanging in Mantua between 1852 and 1855 by order of the Governor-General of Lombardy-Venetia, Field Marshal Josef Radetzky, accused of inciting desertion.

Around 1860, the structure was demolished and the Habsburg prison of San Tomaso, the building that stands today, was built from scratch.

With the transition to Italian state administration, the building became the headquarters of the Territorial Division and subsequently of financial offices.

The museum opened in February 2022 after extensive restoration work on the building.